Vol.135_Renaud Bézy

Renaud Bézy

Interviewed by Kim Kieun

From Paris, France

"I’d like my paintings to be dancefloors."

Please introduce yourself.

My name is Renaud Bézy, I’m an artist living and working in Paris, France. I define myself as a painter, although I do also films and other stuff, but painting is really important for me. It’s at the core of my artistic process: everything comes from it and eventually returns to it. What else there is to say? An important thing for me is that I have been studying at Goldsmiths College in London; those years abroad had a lasting influence on my art practice.

I could see that you repeat the motif of the vase in your work, both in a figurative, but also in a symbolic way. What does this leitmotif mean to you? Yes, vases but also flowers are important in my work. They are tropes, almost stereotypes in painting. People doing amateur painting will automatically turn to those kind of “themes”: the flower pot. For me, it all started with a series of 20 small flower pot paintings that I did around 2009. I painted those from the vague memory and imagination of a forgotten moment of French art history: Montmartre paintings from the 1950’s. It is a postwar moment when miserabilism was “the thing” and France and Europe were completely loosing their artistic leadership. The most famous artist of that period was Bernard Buffet, but my paintings were made using many styles. Nobody wants to look at this kind of art anymore now, but I was interested to force the viewer to look not knowing how to look. That was the reason why I had to paintings those small, depressed, painting with sincerity, with a sense of honesty. They had to have the quality of a painting (not a joke), to look like they were made sixty years ago and I had just bought them from the flea market. What do you make of art when there is no more theoretical framework to look at? I guess that was part of my interrogations and it’s connected with my ongoing personal interest for the overlooked, the vernacular, the rustic, the outdated. Eventually the bad taste is always the taste of the others. After that I decided to stick to this flower pot motif and see if I could get it somewhere else, to a level of celebration and joy. A lot of my work is indeed about performing the stereotype – a stereotype is a dead form – so I guess my work is like revitalizing stereotypes, giving them a second birth. It’s also very comfortable to use those forms that have been painted by so many artists: there’s a great sense of liberty there, it’s like you got a passport to enter the history of Western painting…

a n d t h e n i t ’s y o u r p l a y g r o u n d , you can do whatever you want.

Can you explain your experience in Tahiti? How did it impact your practice?

Being an artist means you always want to see what’s going on around the world. In 2014 I was invited in Shanghai by Paul Devautour, an artist who created an experimental art school in China: the École Offshore. I also had a stipend to go to Tahiti, so I flew directly from Shanghai to Papeete. It’s hard to imagine a more striking contrast, from the ultra modernity of Shanghai to the beautiful quietness of the Polynesian islands. I wanted to go to Tahiti because I was curious about Paul Gauguin and his quest for primitivism. But of course I was also very well aware that those islands are now fueled with mass tourism, the raw beauty that Gauguin was pursuing had been turned into a Disneyland cliché for infinite holidays. So I had these mixed feelings before going there… and the funny thing is that as soon as I set foot on the island, my reluctances disappeared completely. Of course there is a luxurious resorts for tourists and so on, but I was lucky enough to discover so many interesting people, individuals that decided to live their life the way they want; I was also quite moved by the personality of the Polynesians. Other aspects, specially for a painter, are the colors and light there. Again, it sounds like a cliché, but it’s true – in Tahiti, the light is so strong that colors look like an hallucination, really. The shapes of flowers are crazy, too, very geometric. So I decided to try to catch this light and the colors, and put those into my paintings. When I unfolded the Tahitian paintings back in my Parisian studio, I was disappointed: the result was far below my visual experience. But this semi-failure had eventually a very positive effect on me because I then decided to stick to color, and push it to its maximum by introducing fluorescent pigment in my paintings… and then it’s your playground ,you can do whatever you want.

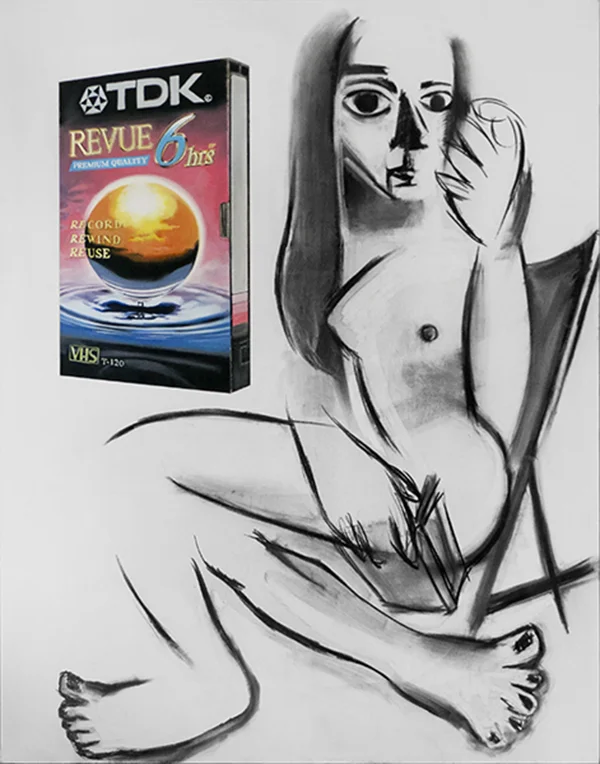

Looking back to your early works and coming toward the current ones, I could see you are interested in moving images as well. How does this switch function for you?

I did a series of films titled Barbarian Ballets. It’s an ongoing project where I impersonate a painter, a different one each time, with different costumes. The costume is very important here, as well as the space where the action takes place. In most of my film I play with the myth of romanticism in painting using beautiful surroundings (i.e. great natural landscapes, Vasarely’s Art Foundation, Moorea Island in the Pacific Ocean). There’s also a sense of burlesque – I’m very influenced by the slapstick movies. My costume, the strangeness of the situations (a huge painting in a landscape) give a a humorous tone that gradually disappears. I try to confront the viewer with a sense of perplexity, starting with a laugh and then slowly not knowing what she/he is looking at anymore. The films are produced with very little money and the help of friends. And I want to keep it that way, with this DIY quality, slightly offbeat. The shooting is a joyful collective moment that forms a good balance for me with the work in the studio that requires endurance, consistency and solitude. In the films I paint without the burden of painting (laughs)! My last Barbarian Ballet is titled “a procession”. It is slightly different from the previous ones as it’s not a depiction of the act of painting. My new idea was to show an episode of a painter’s life, so I decided to start with the end: the funeral. But it’s a joyful film shot in the countryside, in the center of France with animal farms transporting paintings and the local village brass band in uniform playing “Stand by me” by the Beatles. Anyway, the whole thing is also inspired by the funeral of the great Russian painter Malevich.

.

.

.

You can check out more images and contents through our magazine!